Part 2: Crypto Magic

This piece is part 2 of a series about cryptography on the web. It outlines the building blocks, following up the first part, which explained why cryptography on the internet is needed in the first place.

I. Overview

From the outside, cryptography is very much like magic. Unlike the magic in Harry Potter which mostly works with things, however, cryptography works with data. Admittedly, that’s not as cool, but it is real and used billions of times a day all around you. Most importantly, you can actually learn it and use it yourself.

Crypto algorithms can do much more than encrypt things with a password. They can allow you to compare code words with someone without revealing what they are, or allow two people to figure out who holds a bigger number without finding out anything about the other’s. We can look at those later. For right now, let’s look at the crypto systems behind this green lock:

What that lock means is that even if you’ve never talked with anyone at Amazon, nor communicated with any device controlled by them before, and even then, if you talk to Amazon only through a chain of untrusted links, you are assured of two things:

- that your computer is talking to Amazon, and

- that no intermediary in the chain connecting you knows what is said.

To begin explaining how this is possible, we first need to drill down into two fundamental building blocks of crypto: symmetric and asymmetric cryptography.

II. Symmetric Cryptography

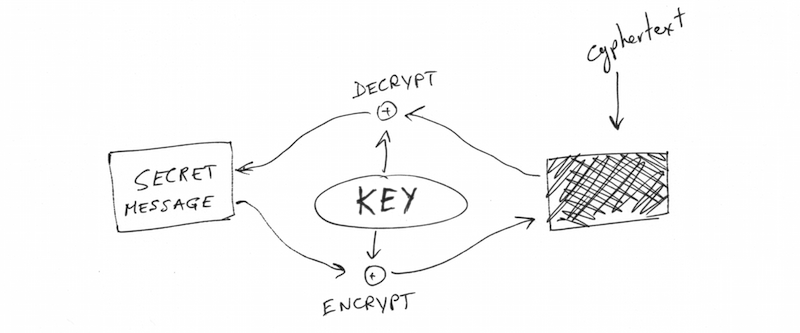

Symmetric cryptography is the older and simpler of the two. It uses a password to encrypt and decrypt data, where encrypted means the information is hidden from anyone without the password. Such encrypted data is called cyphertext, and to someone without the key, it’s indistinguishable from random noise. Unlike some TV shows might lead you to think, modern encryption with a long password is most likely not breakable in any reasonable amounts of time. This might change with future technologies, but it’s definitely unbreakable with today’s.

Since the password used is not actually a word or even anything humans ever look at, it’s called a “key”, instead. When you check your Amazon order history, your computer and Amazon’s server have a shared secret key that nobody else knows, and encrypting and decrypting things with that keys is very fast.

As we pointed out in the first post, the connection to Amazon is going through a chain of other not-necessarily-trusted computers. So how do you share that key and still keep it secret?

The short answer is simply “math”. It’s not proven beyond all possibility, but as far as we can tell, there’s an algorithm that would let you and your friend shout a few big numbers at each other across a crowded room and come up with a shared secret that nobody else knows, even if they’ve heard every word. That’s what computers around the world do billions of times a day and it’s called the Diffie–Hellman key exchange (or DH for short).

While this makes sure that your computer is talking over a channel secure from eavesdroppers, it still does not authenticate whom it’s actually talking to. For that, we need another kind of cryptography.

III. Asymmetric Cryptography

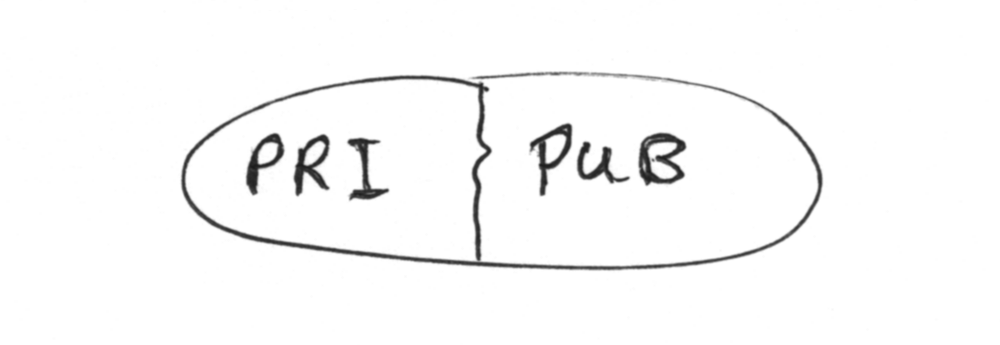

Asymmetric cryptography uses pairs of keys that have a special bond. One is the private key that you keep secret (like a password). The other, which is generated from the first, is called the “public key” and you give it to anyone who wants it.

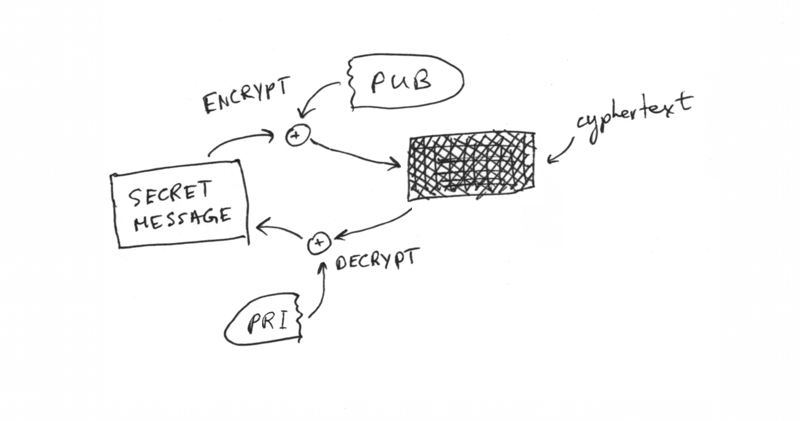

Their bond makes two algorithms possible:

Asymmetric encryption uses the public key to encrypt some data which only the private key can decrypt.

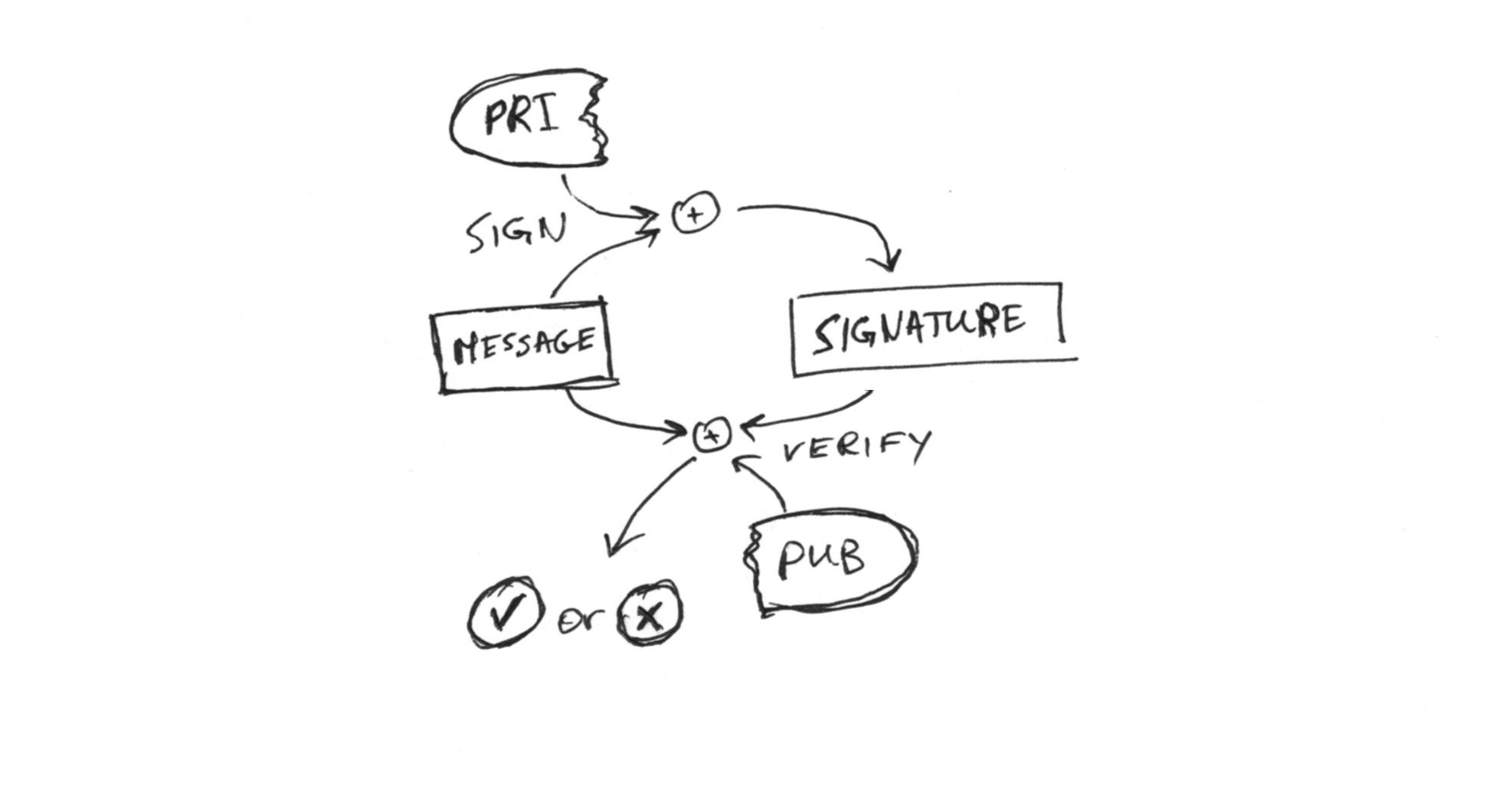

Signing uses the private key and a message to generate a signature that can be verified as legitimate using the public key.

These operations are quite a bit slower than symmetric encryption, but can be quite useful in a pinch.

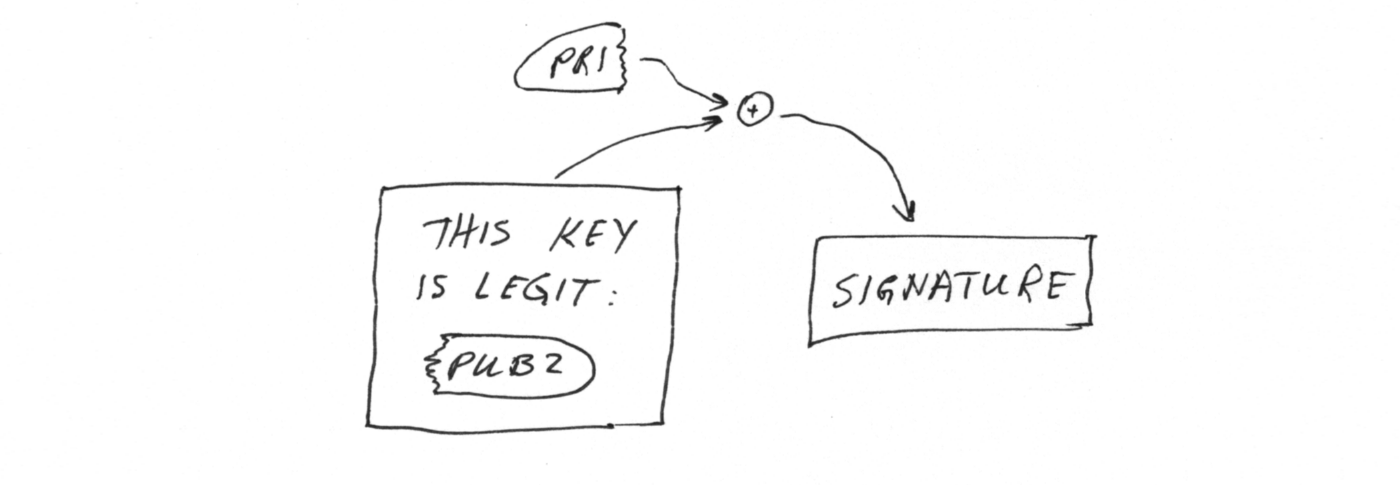

Since public keys can themselves be part of a message, one can somewhat cleverly use the private key of one pair to sign the public key of another:

This is generally called “key signing”, and if you have the public part of the signing pair, you can then verify the signed key as legitimate. Combining multiple pairs in this way is used to create chains of signatures, each valid for signing less than the one before it.

The signature can be bundled with extra data like expiration dates in a format called X.509. This bundle of {explanation, public key, signature} is then called a “certificate”. Using certificates, we can build a more trustworthy chain to verify that we really are talking to Amazon.

IV. Back to the real world

This part explained the building blocks that our mathematicians provide our software. The third part will combine those blocks with the real world. If you’d like to learn about a business with better profit margins than printing $100 bills, read on to Part 3: The Real World (coming soon!).

Many thanks to Aagje van der Meer for proofreading and providing feedback on drafts of this post. The contents of this post are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.