HTTPS Part 1: Chinese Whispers

This piece is the start of a series on cryptography on the web. It explains the reasons we need encryption on the web, and Part 2 explains the basic building blocks used.

I. Behind the Curtain

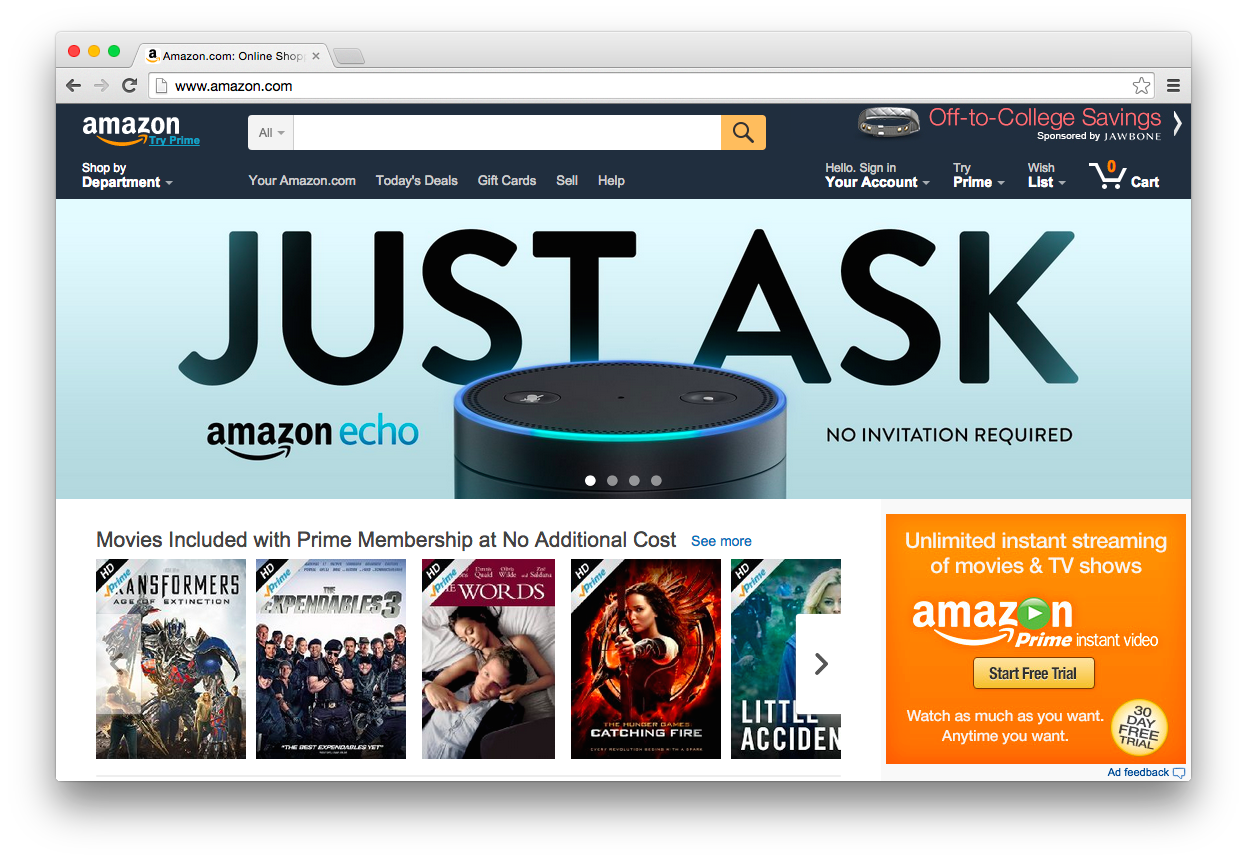

If you type amazon.com into your browser, your computer reaches out to another computer owned by Amazon, which sends back a bunch of code describing what to draw on your screen and what to do when you click and type into the window.

But even though they’re communicating, your computer isn’t talking directly to Amazon’s. It might be accessing the internet by connecting your school’s or work place’s wifi router, which is probably wired to a modem accessing a network controlled by an ISP (like Cablevision or Comcast), which could in turn is connected to a computer actually controlled by Amazon.

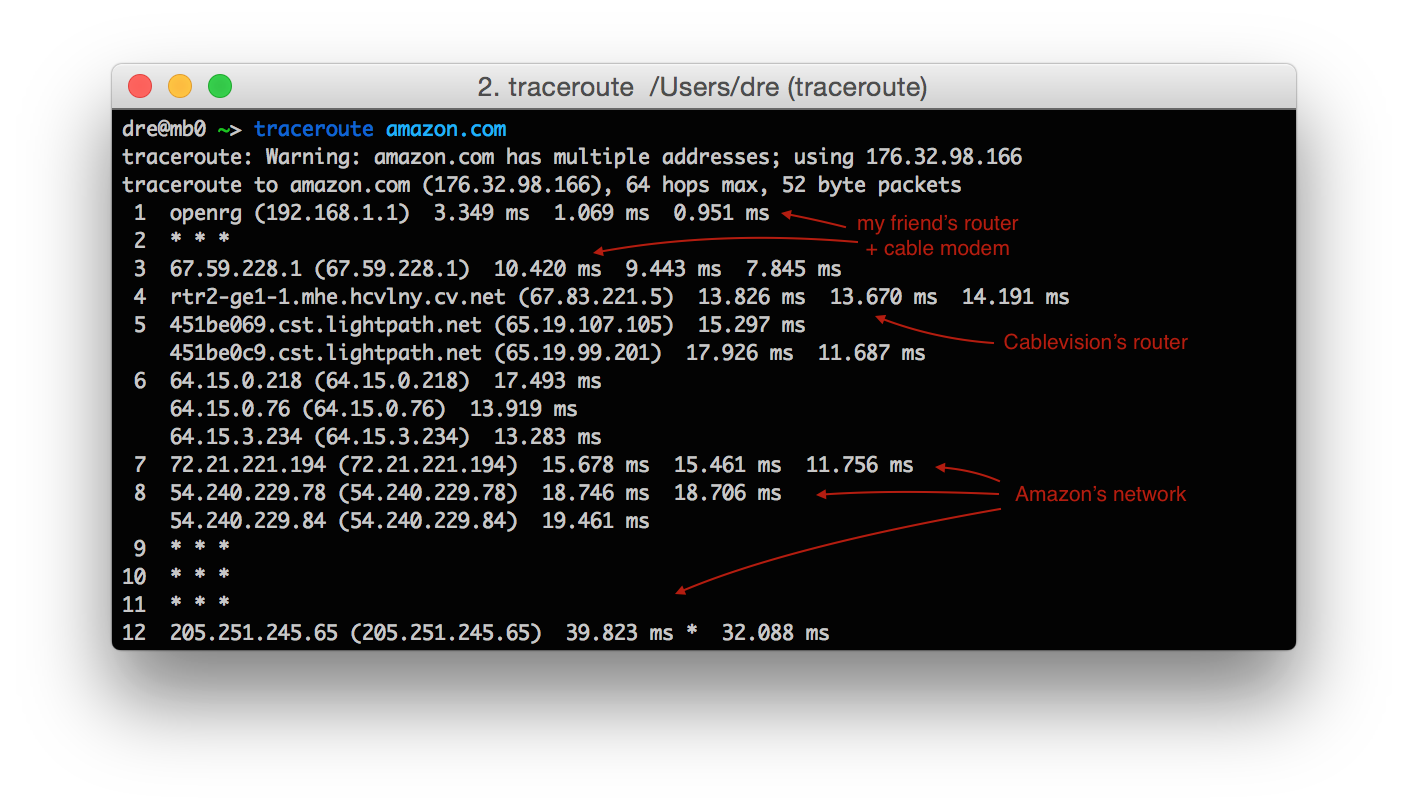

The exact route taken by your messages depends on the networks layouts, congestion, and peering agreements between dozens of companies. The traceroute command in a terminal can tell you some of the hops likely to be taken by a connection, and on my connection right now, it looks like Amazon has a peering agreement with Comcast, since their networks are right next to each other:

(to find out 72.21.221.194 belongs to Amazon, I used the whois command)

All these computers are playing a well practiced game of Chinese Whispers, where everyone is really, really careful not to make mistakes [1]. The protocol, or language, that computers use to talk to each other through intermediaries on the internet is called the Internet Protocol (IP) and can allow trillions of computers to talk with each other. It’s truly one of the great wonders of the technical world.

Even if every intermediary triple checks everything, however, and even if all mistakes are corrected, can we really trust every link in the chain to behave honorably? There are hundreds if not thousands of people with access to this chain who could introduce a bug, whether by accident, or by coercion, or by choice, into systems that not a lot of people can check and even fewer do.

In many parts of the world, state agencies either blatantly control or secretly snoop on the links. While most governments do not admit it publicly, it’s likely that most intelligence agencies in the world who can afford it have similar access.

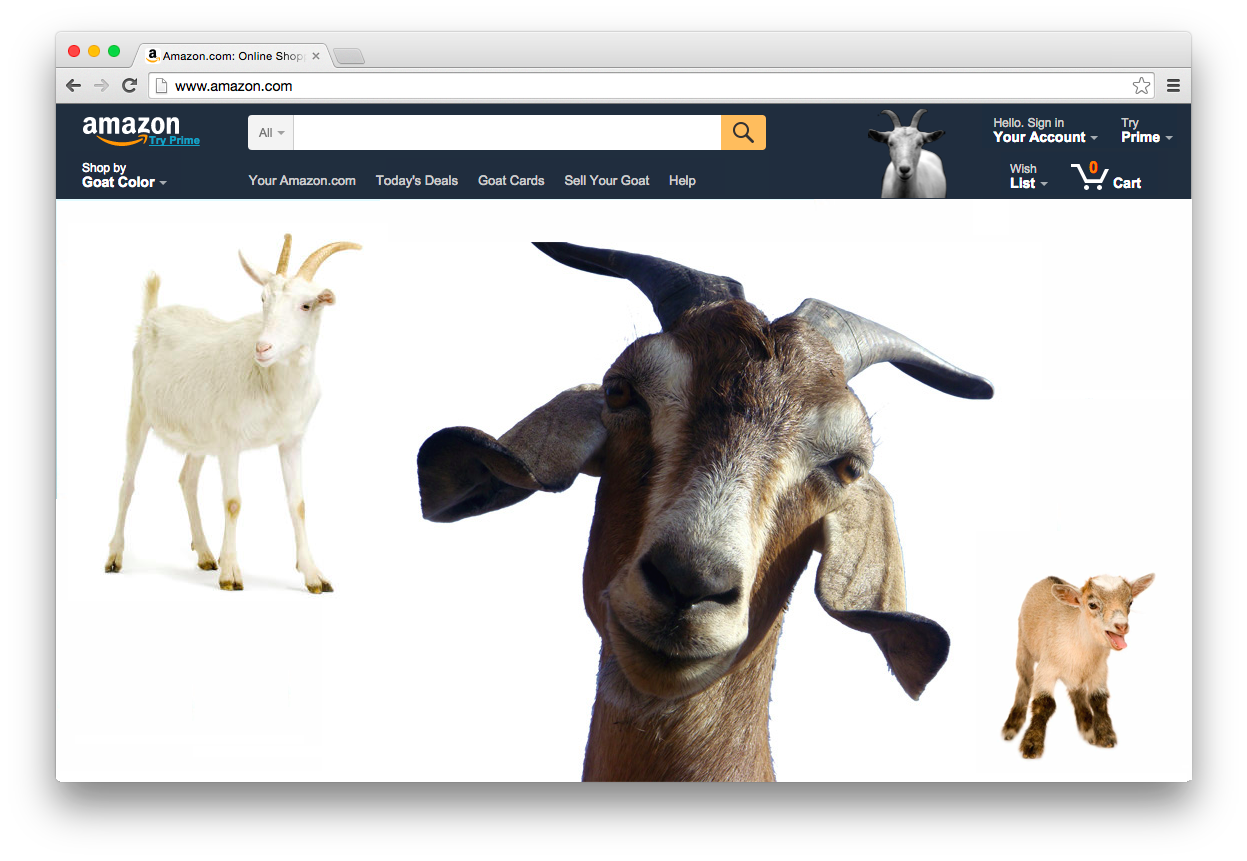

Without extra systems in place, we can’t even be sure that page you load is coming from Amazon at all. Maybe your friend who owns the router likes to joke around, took control of it, and programmed it to respond “yup, just talked to Amazon, and it says they only sells goats now”. There is absolutely no way for your computer to know any better.

Even pranks aside, absolutely anyone can give a wifi network the name of one you trust, and your computer will connect to whatever router has the strongest signal. Like most technology, wifi is built with assumptions of implicit trust, which are reconsidered one at a time as attacks become obvious or are uncovered in the wild.

II. A Serious Problem

For the majority of people using the internet most of the time, this chain of trust works fine, but for a small and very important subset of people and uses, it is not. For example:

- an activist or politician looks at her Amazon reading list in a coffee shop

- the plaintiff to a class action suit emails with his lawyer from the library

- a lawyer connects to his foreign hotel wifi to discuss a negotiation

Even if you are not any of these, as most people aren’t, it is vital for the functioning of nations of laws that more security exists by default for everyone. Even if hacking your email is not valuable to anyone today, it’s hard to predict when it might be in the future. People’s default security levels affect the fundamental fabric of which our society is built.

III. A Wild Cryptomage Appears

Fortunately, this is a problem which already has a mostly effective, if not perfect, solution on the web (although Amazon has yet to turn it on for the front page).

The little green lock in the address bar means that several cryptographic systems are verifying two things:

- you are actually talking to Amazon, even if it’s the first time you’ve ever visited their site on this computer, and

- nobody routing the connection knows what was said, even if they’ve passed on every word [2].

To learn what building blocks make up these systems, venture onwards to Part 2: Crypto Magic.

Many thanks to Jeff Maxim and Joyce C. Clanon for proofreading and providing feedback on drafts of this post. All questions, corrections, and random thoughts are welcome. The contents of this post are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

-

There are many error detection schemes to choose from, and the most effective one depends mostly on the type of connection.

-

Those routing the connection will know metadata like how much was said and between whom, however.